A tale of two approaches: Top Down(US) and Bottom Up (UK).

Offender profiling attempts to describe a tool that aims to narrow the scope of a criminal investigation. This is broken down into 3 key aims (Holmes and Holmes 2002);

1) Identify characteristics of the suspect.

2) Create an evaluation of their belongings.

3) Bespoke interview strategies.

Boon and Davies (1992) coined the labels ‘top down‘ and ‘bottom up‘ approaches to offender profiling. The aim was to distinguish between those that take a more evidenced based profiles using strong data collection strategies to build a picture of the crime from the bottom up as opposed to the notion of a more intuitive application of prior knowledge and experience that is then applied from the top down to the scene. The ‘Top Down’ approach is often cited as being more akin to The U.S -F.B.I methodology and the ‘Bottom Up’ applied to the more distinctive British approach which is often used to describe David Canter’s Investigative Psychology.

However, it could be stated that British profilers such a ‘Jigsaw man‘ Paul Britton could be classed as ‘top down’ due to the profiles he generated from his experience as a Clinical Psychologist and therefore the geographical labels are only as a guide.

The historical roots of the Top Down American Approach

The starting point to profiling arguably goes back to the start of policing itself. The techniques themselves are not new either The work of John Snow (this one did know something!) in the Victorian era using data and deduction to narrow to the source of a cholera epidemic can be seen in the techniques used in geographical profiling today. Jack the Ripper, Hitler had all been the targets of forms of psychological profiling and prediction of future behaviours to allow a strategy to be formed for their plotted downfall. Walter C Langer in his secret wartime report; The Mind of Adolf Hitler famously predicted that Hitler was commit suicide if he rationalised the war was lost. In the text Langer argues;

This is the most plausible outcome. Not only has he frequently threatened to commit suicide, but from what we know of his psychology it is the most likely possibility. It is probably true that he has an inordinate fear of death, but being an hysteric he could undoubtedly screw himself up into the super-man character and perform the deed. In all probability, however, it would not be a simple suicide. He has too much of the dramatic for that and since immortality is one of his dominant motives we can imagine that he would stage the most dramatic and effective death scene he could possibly think of. He knows how to bind the people to him and if he cannot have the bond in life he will certainly do his utmost to achieve it in death. He might even engage some other fanatic to do the final killing at his orders. Hitler has already envisaged a death of this kind, for he has said to Rauschning: “Yes, in the hour of supreme peril I must sacrifice myself for the people.” This would be extremely undesirable from our point of view because if it is cleverly done it would establish the Hitler legend so firmly in the minds of the German people that it might take generations to eradicate it.

source: http://www.iiit.ac.in

James A Brussel and the case of The ‘Mad’ Bomber

However, the work of James A. Brussel is often cited as being the first meaningful ‘Profile’ of the modern era. After a sustained series of bombings between 1940 and 1956 in New York placed in deliberately very public spaces the Police  exasperated turned to local psychologist, Brussel. The profile stated the suspect was most likely middle aged, overweight, and probably not married. It was possible that he lived with a relative, maybe a brother or sister. The offender probably had skills in engineering or mechanics, and may have come from Connecticut or surrounding areas. According to Brussel, he noted that the bomber had a particular grudge against Consolidated Edison, which was New York’s main power company at the time.

exasperated turned to local psychologist, Brussel. The profile stated the suspect was most likely middle aged, overweight, and probably not married. It was possible that he lived with a relative, maybe a brother or sister. The offender probably had skills in engineering or mechanics, and may have come from Connecticut or surrounding areas. According to Brussel, he noted that the bomber had a particular grudge against Consolidated Edison, which was New York’s main power company at the time.

“He goes out of his way to seem perfectly proper, a regular man. He may attend church regularly. He wears no ornament, no jewelry, no flashy ties or clothes. He is quiet, polite, methodical, prompt… Education: at least two years of high school. The letters seem to show that. They also suggest that he’s foreign-born or living in some community of the foreign-born…He is a Slav… One more thing,” I said, my eyes closed tight. “When you catch him—and I have no doubt you will—he’ll be wearing a double-breasted suit….And it will be buttoned,” I said. (Brussel, 1968)

All of this information led police to George Metesky, who was a former employee of Con Ed. In 1957, Metesky was arrested, and surprisingly confessed at once to the bombings. Ironically, Dr. Brussel noted that the bomber would be dressed nicely and neatly. When George Metesky was arrested, he changed into a neat, clean, double-breasted suit from his pyjamas, which he dutifully buttoned.

The 1970’s -onwards

In the 1970’s a melting pot of specialists in serial crimes became the catalyst for how profiling is shaped today. The Federal Bureau of Investigation started to develop its own profiling techniques, Howard Teten and Patrick Mullany were key members of the newly formed Behavioural Science Unit. In addition to this Robert Keppel and Richard Walter published a manual called ‘Profiling Killers’ partly based upon their wide experiences of working within Michigan prisons. Ressler, Burgess and Douglas started to develop the idea of a typology of serial offenders.

Watch the following video clip that discusses the start of profiling in the 1970’s with an interview with serial killer; John Wayne Gacy.

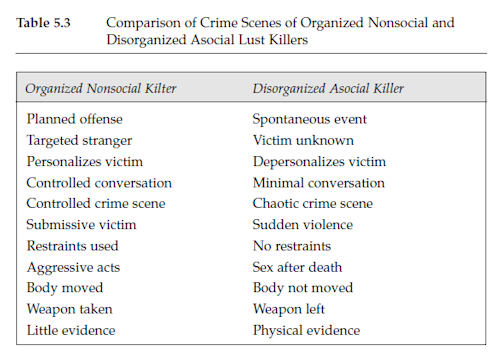

After interviewing 36 of America’s most dangerous serious offenders, they identified key characteristics that would allow law enforcement agencies to ‘read’ a crime scene that correlated with a type of individual and their stereotypical behaviours summarised below into the organized and disorganized typologies.

Watch the video clip that summarises all approaches of profiling with a focus on the Top Down typologies.

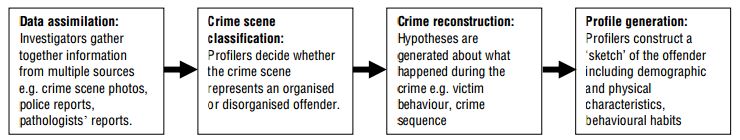

Howitt (2009) identified a key 4 stage process to the approach;

However Dr Tom O’ Conner suggests;

This classification stage of analysis is, however, considered unnecessary by those who: (a) advocate inductive (or non-FBI) methods; or (b) find that there is no empirical validity or reliability from classification. Godwin (1998) and Canter et al. (2004) are representative of those who consider classification along FBI lines to be invalid. Nonetheless, the FBI method of classifying the basic “type” of the offender early on has existed since 1974 for good reason. Douglas, Ressler, Burgess & Hartman (1986) recount successful use of the method, best explained in Ressler, Burgess & Douglas (1992), as having value for narrowing down, early on in investigation, a possible list of suspects quickly sorted by psychological “indicators,” much like the DSM-IV checklists used in counseling psychology (Douglas, Burgess & Ressler 1997). The FBI method involves classifying offenders very narrowly by whether they are “disorganized” or “organized,” and not only is there debate over whether these terms have any utility, there is debate over whether these two categories are a typology, a dichotomy, or a continuum (Turvey 1999). Essentially, they are substitute terms for psychotic (disorganized) and psychopathic (organized); i.e., watered-down psychiatric terms for the benefit of law enforcement training. Most of all, they are generalizations, not conclusions. An offender, so categorized, only “tends to” have the characteristics associated with their type. No magical capture of the offender is expected from use of this typology.

Case Study -The Washington Sniper

Watch the following video clip using the infamous ‘Washington Sniper‘ case and consider how the experience of the individual profiler can produce contradictory perspectives creating an obstacle rather than a useful tool for law enforcement agents.

Profiling today.

There has been much criticism of the F.B.I approach on a number of fronts in terms of its reliability as being fit for purpose. As it tends to be used for serial cases which are high profile its successes and failures are often well documented, warts and all. In addition many academic evaluations have been performed on the accuracy of the typology with existing, retrospective data arguably the most damning is that of David Canter’s paper of 2004 which statistically analysed solved cases and how they correlated with the typologies. Only two of the characteristics provided any correlation.

Read about Professor David Canter’s own approach to profiling here.

Exam based resources

- Answering questions; Click the link for an example of how to respond to an exam question.(A2 OCR)

- Overview of the Top Down approach for revision.

- Overview of the Bottom-Up approach for revision.

Other Resources

- A short article reviewing the usefulness of offender profiling.

- David Canter’s evaluative analysis on the reliability of the typology approach.

- Classic review of profiling. What’s behind the smoke and mirrors?

psychologist at Broadmoor Hospital has made arguably some of the biggest contributions to Psychology. Guðjónsson has had a hand in some of the most significant interventions Psychology has made in the U.K particularly as his role as an expert witness in

psychologist at Broadmoor Hospital has made arguably some of the biggest contributions to Psychology. Guðjónsson has had a hand in some of the most significant interventions Psychology has made in the U.K particularly as his role as an expert witness in

ion from a guilty suspect.

ion from a guilty suspect.